API access to public conversations before, during and after any calamity can help authorities and volunteers to rescue more people.

As extreme weather unfolds across the globe, one increasingly important way to provide instant crisis alerts, relief efforts, and assessment of the ground situation is through analyzing social media chatter.

Following natural disasters — including the Jakarta flooding in Indonesia, Australian bushfires, and Typhoon Hagibis in Japan — social media platform Twitter worked with its official partners and various authorities to help local communities to share resources, raise funds and rally around one another.

Tweets create a wealth of social data that can be used to understand the calamity at hand, and also provide general climate change trends and sentiments across populations. Policy makers can use tweets to provide aid in more expedient ways while setting guidelines and improving responsiveness for future emergencies.

Tracking the tweets

Twitter provides companies and individuals with programmatic access to its data through public application programming interfaces (APIs) to build apps and tools for drawing insights out of social media conversations.

The platform’s interactive webpage lets users explore how conversations evolve at all three stages of any extreme weather event:

- Before: People tweet about things they notice in nature, such as higher water levels, or drier and hotter-than-usual temperatures. During the precursors to anticipated emergencies people also tweet about their preparations, such as readying their home or neighborhood for a fire, or creating flood or hurricane defenses for critical structures.

- During: As an extreme weather event begins to affect people, people start to raise the alarm on social media. At the apex of such events, conversations about the weather on spike the most as people tweet about what they are experiencing in real-time.

- After: At this time, the conversations on the platform begin to shift towards humanitarian assistance like donation drives for supplies, rescue or medical assistance, and financial contributions to help people in the affected community.

What the data is showing

Recently, the United Nations’ climate science research group (the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change or IPCC) recently concluded that human-induced climate change is already affecting many weather and climate extremes in every region across the globe, including increases in the frequency and intensity of hot extremes, marine heatwaves, and heavy precipitation.

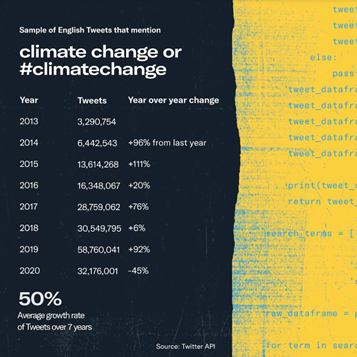

The extent of extreme weather events is also reflected in public Twitter conversations. A sample of English-language Tweets from 2013 to 2020 has indicated that mentions of “climate change” have grown by an average of 50% over those seven years.

By utilizing the vast amount of tweet data from public conversations, developers have the opportunity to build solutions that can help local communities during unforeseen extreme weather events, or study public sentiments about climate change without human bias.

According to the Twitter Developer Platform head of marketing, Amy Udelson: “Developers consistently inspire us with the ways they support people in crisis during natural disasters. The #ExtremeWeather visualization showcases what can be achieved when our developer and partner communities leverage the Twitter API and apply these insights to the public good. We hope this work sparks conversation, increases awareness and creates a connection between those passionate about climate change and disaster relief.”

Tapping Twitter data in APAC

As home to more than half of the world’s population, the Asia Pacific region (APAC) is one of the most vulnerable to the devastating effects of climate change.

Developers who are passionate about building for the climate crisis can tap into public conversations and play a critical role in providing actionable information during extreme weather events and other crises.

Said Twitter’s Senior Director, Public Policy and Philanthropy (Asia Pacific), Kathleen Reen: “(Our) uniquely open (API) service has been used by people all around the world to share and exchange information in times of crisis. We recognize our responsibility in ensuring that people can find the information they need — especially during a natural disaster — and have worked to amplify credible information from trusted media, government agencies, as well as relief and volunteer organizations. Twitter data can be used in real-time to provide vital support to people on the ground, and (to also) raise broader awareness and understanding of the impact of a crisis.”

Three developer case studies

In the January 2020 calamity where record-breaking rainfall inundated Jakarta, Indonesia with more water than its infrastructure could handle, over 20,000 tweets were captured by Peta Bencana to develop a ‘humanitarian bot’ using an open source software called CogniCity.

This bot listened for chatter on the @PetaBencana account containing flood- and disaster- related keywords such as “banjir” (meaning “flood”). It then automatically responds with instructions for uses to share observations, using this information to create a flood map.

The flood map was subsequently accessed over 259,000 times during the peak of flooding, a 24,000% increase in activity within a week. Residents checked the map to understand the flooding situation, avoid flooded areas, and make decisions about safety and response.

The Jakarta Emergency Management Agency (BPBD DKI Jakarta) also monitored the map to address resident needs and coordinate rescue response based on reported severity and need. As waters receded or support arrived, they kept the flood map up-to-date.

In the Australia bushfires raging inJune 2019 to March 2020, Brandwatch analyzed the tweets of 2.8m people around the world, and a total of nearly 10m public tweets from December 2019 to March 2020. The data led helped to unite communities over mutual aid and fundraising efforts such as #AuthorsForFireys auctions and the ‘Find a Bed’ movement to find emergency accommodation for those displaced by the bushfires.

Within a week of its launch, Find A Bed had accrued 7,000 listings and housed around 100 people, including a 104-year-old who lost her house.https://digiconasia.net/wp-admin/edit.php?post_type=carousels

Finally, the devastating Typhoon Hagibis in 2019 caused more than 20 rivers in Japan to overflow quickly. Inhabitants were forced to leave their homes for higher ground. A Twitter Official Partner, JX Press, analyzed the platform tweets to detect keywords related to the crisis to provide fast alerts, averaging 20 to 45 minutes before many Japanese news outlets.

With access to such dynamic real-time data, governments can act more effectively during emergencies, prioritizing the right level of help to the right places at the most expedient pace.